MASS SQUATTING AS POLITICAL PROTEST

by Keith Salter

By the mid-1980s poverty had become rampant throughout Australia. As jobs moved overseas and mortgage rates skyrocketed above 15%, many people suffered under this unbearable weight. Some lost their homes and had to start again as renters in a new suburb. Others, overwhelmingly young people under 30, working with a handful of experienced squatters, took control of their destiny and moved themselves into vacant properties in large numbers.

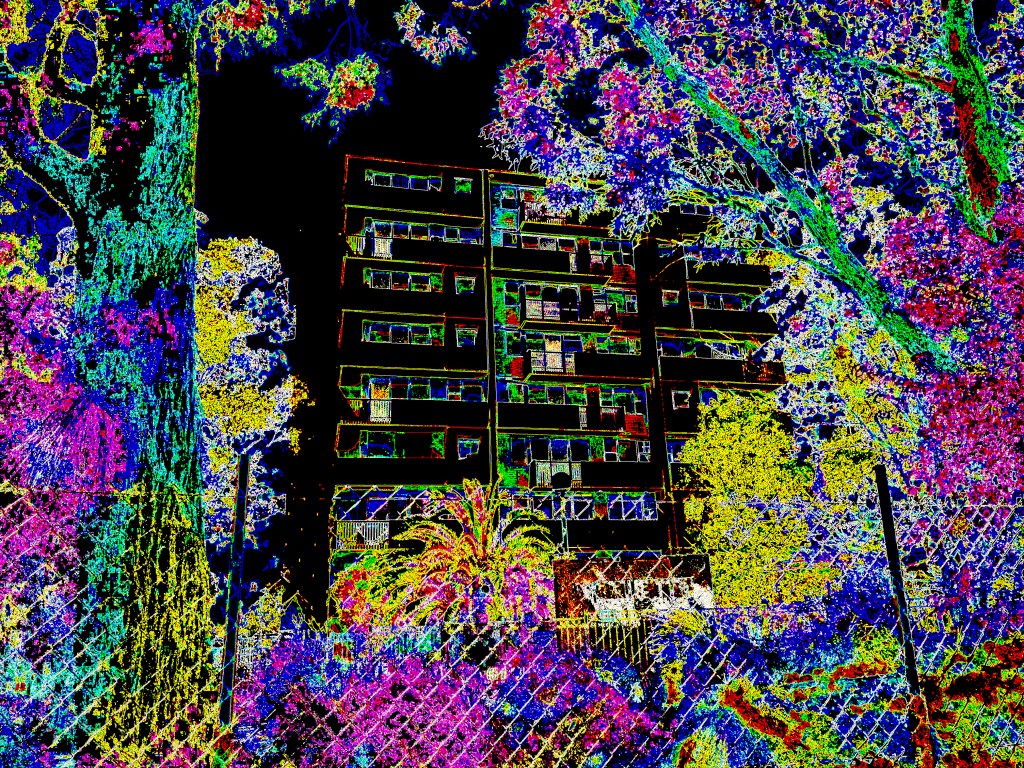

The residential properties had sat empty for years prior to these actions. They stood in forlorn clusters and were therefore highly visible, making them a prominent sight at street level. They gathered dust and grime and sometimes became receptacles for rubbish. The squatters changed all of this for the better when they moved in. Rubbish was removed, frontages were swept, and windows were wiped clean.

Mass squatting observes that there is safety in numbers. That many hands make light work. That good ideas and strategies are often the product of kind spirited group discussion. And that people power is a collective endeavour that requires all hands on deck.

Mass squatting became the primary means of long term protest in Sydney during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Whilst somewhat famous – or notorious – mass squats such as the Gunnery (Woolloomooloo) and the Warehouse (Redfern) remained active for many years, others disappeared rather quickly.

But that was to be expected, as many of these short-lived mass squats were planned and organised as public actions to highlight the plight of homelessness within Australia and the sheer lack of viable living arrangements for many people.

A significant aspect of the mass squatting action was designed as spectacle to highlight a serious social problem that both government and charity could not or would not resolve. This type of mass squatting saw banners unfurled from squatted buildings, megaphone commentary delivered from the balconies of squatted properties, and temporary barricades sometimes erected within the properties themselves to discourage random interlopers or intermittent police intrusion.

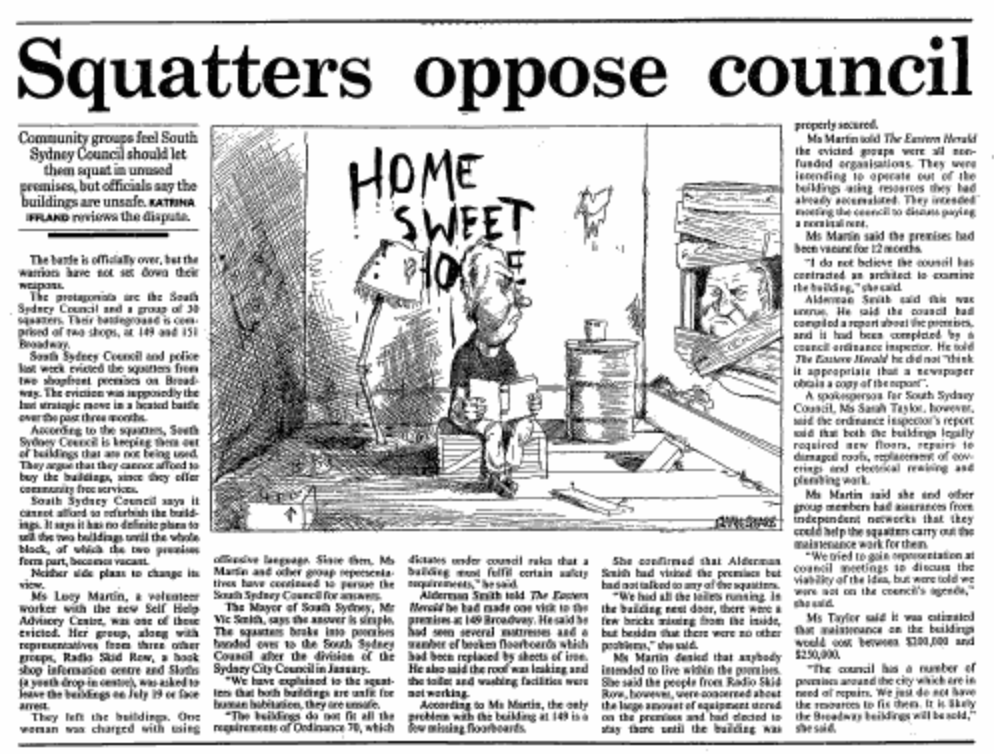

Squatters oppose council. The Sydney Morning Herald. 27th July 1989. (109).

During the mass squatting action, excellent internal communication ensured squatters remained present onsite at all times. This included overnight stays, which was often a lot of fun. A camp kitchen was installed, and fresh produce was transformed into hot meals doled out to the hungry, which is usually everyone during such busy days.

Between the more serious moments that included the odd media interview, police and council liaison, and local community door knock, a convivial and rather festive mood permeated the squatting enterprise.

MASS SQUATTING IS DIRECT ACTION

Mass squatting remains an ideal form of protest within our modern society. This is because mass action that persists for longer than a day is what is needed to bring about genuine social change. The act of mass squatting challenges the existing harmful system of property relations that keeps people down and poor. And, simultaneously mass squatting pushes back against the absurd and degenerate cultural practice of land banking, which continues to plague our communities and ensures that properties remain unoccupied.

Mass squatting takes on the rich snobs who view abandoned properties as investment trinkets. The hypocrisy of government, industry, church, and the national ruling class (all possess extensive property portfolios) in leaving both domestic and commercial properties in a state of abandonment for many years is highlighted through the direct action of mass squatting.

Mass squatting contradicts the MSM narrative that says the property market is nothing but gleaming smiles and endless profits. And, the optics of mass squatting serve as meaningful contrast to more than a few prominent property sales websites.

Most importantly, mass squatting directly and immediately houses the homeless and teaches them life skills which they can use again and again. Mass squatting is the doomsday prepper lifestyle without the doom and gloom or the firearms fetish.

Mass squatting requires an entrepreneurial spirit, a willingness to innovate, and a preference for disruption over conformity. For most squatters the rationale runs something akin to this: the empty houses are right there, and you are right here, and the only thing that stands between the two is attitude. Either you do as you are told and fail, or you break a taboo and overcome social stigma, think for yourself, and have a go at reaching for success. When compared with the tens of thousands currently sleeping rough, it is rather obvious that squatters are indeed successful individuals.

VIEW THE EMPTY PROPERTIES REGISTER

When homelessness becomes so widespread that large groups of people become interested in squatting an as antidote to the vast lack of suitable accommodation, then our society has taken a turn for the better after taking a turn for the worse. When this occurs, it can be deduced that a useful awareness of class privilege and power relations has arrived.

The ethos behind squatting abandoned properties is the firm belief that everyone should have a place to call home. Squatting relies on non-violent direct action that is revolutionary in nature, precisely because it upends the traditional property relations of predatory capitalism. Mass squatting requires some serious preliminary discussion, followed by planning, organisation of both material resources and people, collaboration, consistent effort, patience, and the correct spirit in hand.

Mass squatting remains a significant means to advance a programme of direct action in relation to accommodation and housing. Which in turn, is likely to contribute positively to reducing the effects of the housing crisis in Australia.

Photo & artwork | Keith Salter

Leave a comment